MARION, Ill. — One of three developers entrusted by state and city of Marion officials to oversee a multimillion redevelopment project — a key to the region’s economic health and publicly backed by a $112 million bond deal — was on the verge of being sued for millions of dollars before ground was broken, court records show.

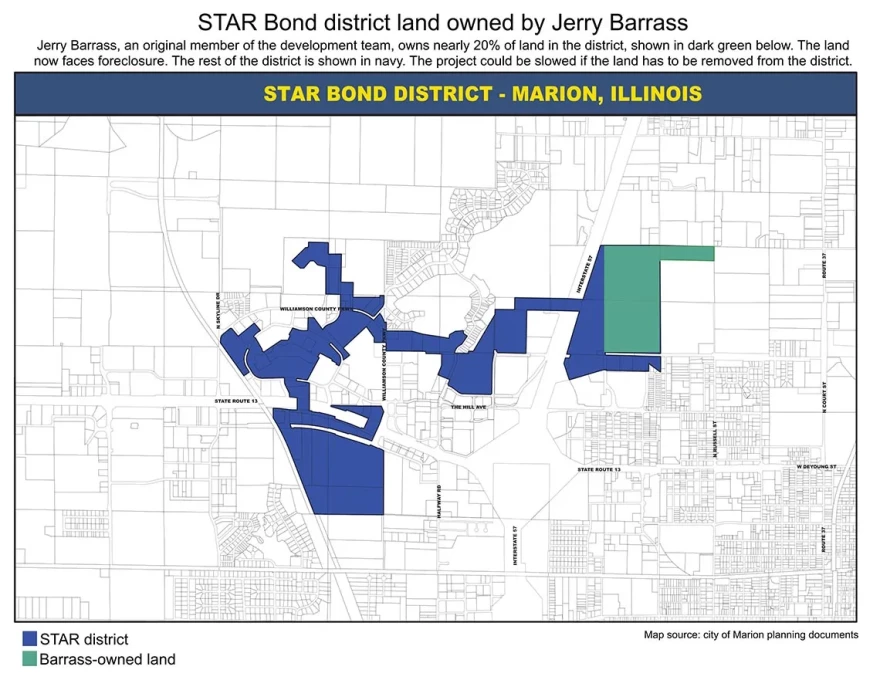

Jerry Barrass, an original member of the three-person master developer team and the main contractor on the taxpayer-supported Sales Tax and Revenue or STAR Bonds deal, owns nearly 20% of the land in the 466-acre project — land that now is being foreclosed in one of the slew of lawsuits Barrass faces that seek millions of dollars in unpaid debts. The outcome of the foreclosure and the property’s continued inclusion in the district could complicate the project’s future.

The redevelopment plan — aimed at revitalizing a stagnant shopping mall and creating a large entertainment, shopping and sports venue district — doesn’t call for building on Barrass’ land in the initial stages. But a sale in the foreclosure case or the removal of the property from the district could require the city to do another feasibility study and sign off on a revised project, under state law. The remaining partners — local businessmen Rodney Cabaness and Jeremy Shad Zimbro — say they bought Barrass out of his 10% ownership of the project and insist it is proceeding full steam ahead after they have taken responsibility for the construction.

So far, nearly half of the $112 million in bond proceeds has been spent on the project. Cabaness declined to provide letters of intent from any major retailer committed to opening in the district to Illinois Answers Project and Capitol News Illinois, citing nondisclosure agreements. But Marion city officials said they are not concerned and said the project is proceeding as planned.

Marion Mayor Mike Absher said in an interview the project aims to lure tourists to visit and stay in southern Illinois, with the initial phase including construction of a fieldhouse with an interactive golf driving range, a family entertainment center inside of the mall with bowling, go karts and laser tag, and a Hampton Inn hotel, all slated to open next summer.

Developers and local officials continue to try to draw attractions to the project. As recently as June, Marion officials explored attracting a stadium for cricket, a flat-bat game that originated in Britain and resembles baseball. The stadium bid was abandoned after officials learned the venue needed to be within an hour drive of Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport as part of the project requirements. Absher acknowledged the attempt was a long shot and was meant for a later phase of the project.

A well-known local developer, Barrass had played a major role in redeveloping downtown Marion. These days, he’s keeping a lower profile. Reporters couldn’t find him at either his businesses in town or three of his homes. His father said he didn’t know where he was but offered his phone number. After a brief interview with a reporter, Barrass hasn’t returned multiple phone messages. Neither he nor his attorney has responded to a certified letter with questions about the project and his finances.

“You’d have better luck trying to catch the wind,” said an employee of one of Barrass’ companies who reported sightings of either Barrass or his truck in mid-September when reporters visited.

Barrass and his companies face more than a dozen lawsuits from banks and other creditors, almost all of which were filed in recent months. His financial woes appear to have come as news to every major player in the project. State officials responsible for approving the $112 million bond deal said they learned of it when a reporter told them. Cabaness pleaded ignorance of Barrass’ problems. And the city of Marion said it relied on the partners’ ability to finance the deal as proof of their stability. One of the banks that financed the deal is now separately suing Barrass.

At least one of the lawsuits is related to property Barrass owns within the Marion development. Cabaness and Zimbro, who brought Barrass into the project as a co-developer and the main contractor, are now responsible for managing contracting on the project as well as ensuring its overall success. He’s been bought out of the project, though he and his companies have been reimbursed for construction work.

Civic leaders entrusted Barrass, Cabaness and Zimbro with developing an attraction city and state officials said would attract out-of-state visitors and is required under state law to create 1,500 new jobs, plus 5,000 construction jobs. The project promised to change the economic landscape of the region and bring at least $100 million in annual gross revenue to southern Illinois, where residents of cities like Marion have felt the effects of a weak economy and sluggish population growth.

Local officials backed the project by issuing more than $112 million in municipal bonds — called STAR Bonds — to be repaid with future sales tax revenue from the redevelopment area and by building infrastructure like sidewalks, sewers, streets and road improvements.

“Endless” economic potential; early financial turmoil

The Marion project is the first for which STAR bonds are being used in the state, but the financing tool may soon be used statewide after the governor signed legislation into law on Friday.

The bonds, modeled after an initiative with the same name in Kansas, were created by Illinois law more than a decade ago to allow governments to pay for construction, land acquisition and other project costs with future sales taxes generated by the development. The bonds are fulfilled in 30 years but payments must be every six months.

STAR Bond districts differ from what local or state governments would typically finance, such as improving roads, building sidewalks or cleaning up a polluted site. STAR Bond proceeds can be used to buy real estate, pay for construction and more. If the major attraction of the project was an amusement park, the bonds could pay for a rollercoaster, for example.

Gov. JB Pritzker heralded the STAR Bonds investment with a visit to the area in May and touted it as “a bold plan to turn an old shopping mall into a world-class entertainment destination.”

“The economic potential is endless,” Pritzker said.

But the project, less than a year after breaking ground, has already hit its first hurdle.

Within weeks of the governor’s visit, Sterling Federal Bank filed a foreclosure action on land owned by Barrass, including 90 acres within Marion’s STAR Bonds district. Court documents show Barrass asked on June 10 for 45 days to make arrangements for a “non-traditional lender” to purchase the loans. Tom Carley, a former banker now acting as Barrass’ financial advisor, said in August he was working on securing alternate financing to resolve the foreclosure, but stopped returning reporters’ phone calls. The foreclosure case is pending.

In addition to the foreclosure action, Barrass allegedly owes millions of dollars in unpaid debts and mortgages tied to his businesses and farm, according to court documents. At least seven other banks have filed collection and foreclosure actions against Barrass in recent months. Three tax cases are also pending and a local union has sued Barrass in federal court for his alleged failure to pay employee benefits. The state of Illinois filed a lien against Barrass at the end of May for $42,220 for owed taxes.

Cabaness said he wasn’t aware of Barass’ money troubles before the suits were filed.

“I know very little about his personal finances,” Cabaness said in an August interview.

Under the law that created STAR Bonds, the project required a feasibility study as part of the vetting process. Chicago-based Johnson Consulting assessed the plan’s financial promise but did not investigate the three men behind it and the master development company, Millenium Destination Development LLC. To become the master developer for the project, Millenium had to show creditworthiness to the city of Marion by providing a letter from a bank testifying to the company’s financial health or evidence of the ability to finance at least 10% of the project.

Cody Moake, chief of staff to the mayor, said the city first relied on a letter from 15 years ago regarding then-master developer, Bruce Holland, who’s no longer involved in the project, stating Holland “meets high standards of creditworthiness and financial strength.” Then, during the bonding phase, Moake said the master development company, headed by Cabaness, proved they could fund at least 10% of the project, using a combination of loans.

By the time the lawsuits against Barrass were filed, the city had already approved and issued $112 million in bonds. According to the bond offering documents, one of the banks that offered Marion Center Project LLC, where Barrass was a principal, a $4 million credit line in 2020 has since filed foreclosure action against Barrass’ property.

When reached by phone in August, Barrass said he no longer is involved in the project. He denied the foreclosures had anything to do with his exit from the project and declined to explain further.

His former partners, Cabaness and Zimbro, said they wished him well but declined to comment further or provide any information about the future prospects for Barrass’ land in the district. Barrass owned 10% of the shared development company in 2020, the same amount as Zimbro and two other partners, Ryan and Chad Holland, the nephews of Bruce Holland, the former owner of Millenium Destination Development LLC. Cabaness owns the remaining 60%.

Barrass’ land, including the 90 acres currently in foreclosure, is part of the district but Moake said it is not a part of the current STAR Bonds project. Barrass’ land was included in the district in case there are future phases of the development, Moake said.

The Illinois STAR Bonds legislation tasks cities like Marion with appointing “master developers” for projects in the STAR district. Marion City Council first approved Millennium as the developer in 2010. The company was reappointed in 2020, when Barrass became involved, according to state business records.

The vision for the Marion STAR Bonds project

The STAR Bonds concept in Illinois was born in the Metro East in 2009. Bruce Holland, chief operating officer of Holland Construction, along with partners John Costello, son of then-U.S. Rep. Jerry Costello, and Holland’s nephews, Chad and Ryan Holland, proposed a $1 billion development called University Town Center in Glen Carbon that included retail, hotels and a Legoland amusement park.

At the time, Holland touted STAR Bonds as key to the development. The Metro East project collapsed in 2010 when the sponsor of the bill required to establish STAR Bonds pulled his support after local legislators and mayors voiced opposition, citing studies that found STAR Bonds could adversely impact existing businesses.

But lawmakers, led by a contingent from southern Illinois, passed the bill on the last day of the General Assembly in 2010, moving the project from Glen Carbon to Marion, citing higher unemployment and fewer competing businesses there. The original STAR district, created in 2010, included only the land now owned by Barrass and others, but was amended multiple times beginning in 2012 to remove and add properties, including the mall.

Only six communities in southern Illinois grew in population between the two most recent U.S. Census surveys. The city of Marion’s population remained relatively flat in the same time period. In Williamson County, where Marion is the county seat, 14% of people live in poverty. The median income is about $61,000 per year. People 50 and older make up 40% of the population. The unemployment rate is about 4%, close to the national unemployment rate.

In addition to the developer appointment, Cabaness and Zimbro also own the company behind the destination user in the development, Oasis Outdoors, which includes powersports, RVs, manufactured homes, entertainment options and event space. In a letter of intent, the developers envision Oasis will use more than 300,000 square feet of warehouse space for holding products with an equal amount of ground floor space and offices on the upper level of the mall. The setup will allow customers to test-drive products and take them home the same day, which the developers highlight as a unique and attractive feature.

A February report on pledged STAR revenues said the Oasis components “are complemented by the proximity of Black Diamond Harley Davidson (outside the STAR Bond District), owned and operated by an affiliate of the master developer.” Black Diamond Harley Davidson is owned and operated by Cabaness and Zimbro. Since that report, plans changed, and Black Diamond Harley Davidson will open a store inside of the mall.

In August of this year, Cabaness and Zimbro announced they would close Roadhouse Harley Davidson in Mount Vernon. He attributed the closure in Mount Vernon, which is less than 50 miles from Marion, to consolidations initiated by Harley Davidson.

Harley Davidson, Inc. reported declining revenues and profits last year. Cabaness said the Mount Vernon store closure was the “right business decision,” and that it would help them focus on the Harley Davidson store and the rest of development inside the centerpiece of the project — the old Illinois Centre Mall.

Over the last decade, the Illinois Centre Mall has had few tenants with little interest from developers. Currently, the mall is home to Target and Dillard’s locations, though neither are included in the STAR Bond district, as well as Anderson’s Furniture & Mattress, which is included in the project with a planned expansion. In 2020, Cabaness and Absher, the Marion mayor, were looking at a map of the 2010 STAR district and had an “a-ha” moment to include the old mall, according to reporting from Swinford Media Group.

“This is an incredible opportunity for Marion, and this development will benefit southern Illinois as a whole,” Absher said at the time. Absher owns 1.5 acres of land with an office building that abuts the southern boundary of the district and said he doesn’t anticipate benefitting from the project “one way or the other.”

“I was there before STAR Bonds was, so it’s just an office building,” Absher said. “I don’t generate any business out of that building or anything else.”

How STAR Bonds work

Under the STAR Bonds legislation, private developers are reimbursed for project costs by money from the sale of municipal bonds. The buyers receive payments funded by sales taxes generated by the development. If the project fails or doesn’t generate as much revenue as anticipated, the city of Marion and the state of Illinois won’t lose out on any sales tax already collected — except the opportunity cost of losing potential sales tax revenue from a different development in the same space that didn’t use STAR Bonds.

The main attractions within the STAR bond district must have “an annual average of not less than 30% of customers who travel from at least 75 miles away or from out-of-state.”

The district also includes a prospect league baseball field, Mountain Dew Park, where the Thrillville Thrillbillies play, with more ballfields under construction. The developers hope to bring regional tournaments to the sports complex and provide families with evening entertainment with a go-kart course, a “Top Golf-like” facility, putt-putt golf and outdoor pickleball courts, Cabaness said.

STAR projects and districts in Kansas, where they originated, have had mixed results. Bonds were authorized by the legislature in the 90s, so the state has had more time than Illinois to experiment with their use. The nonpartisan audit arm of the Kansas Legislature produced an audit in 2021 evaluating the impacts on tourism from STAR projects and completed another report three years later to measure the impact on local quality of life.

Some of the attractions in the districts include the Kansas Speedway in Kansas City, Kansas, the Field Station Dinosaurs animatronic attraction in Derby, and the Underground Salt Museum in Hutchinson, which offers tours of a salt mine that’s been active for more than a century.

Most of the projects didn’t succeed in drawing out-of-state tourists and had a lukewarm effect on local quality of life, according to the reports.

A contractor in financial trouble

A portion of the STAR Bonds district owned by Barrass contains piles of concrete, rock, metal and rusted farm equipment. A “No Dumping” sign was posted at the entrance to the land where the debris was found. Some of it tumbled into a lake.

Less than a mile away on a September afternoon, the mall that Cabaness, Zimbro and Barrass bought in 2020 under the name Marion Stadium LLC, was a hub of activity. Concrete and asphalt trucks spread material. Painters touched up the outside.

Cabaness and Zimbro decided to buy Barrass out about six months ago, Cabaness said in an interview in August, after it looked like he “wasn’t going to be able to pay his portion,” but both declined to disclose how much they paid Barrass. The cost of buying Barrass out couldn’t be reimbursed with project funds, Cabaness said, adding that Barrass no longer does any work on the project.

“He was the guy that just had the equipment and the ability to get the construction work done,” Cabaness said.

Barrass and Cabaness continued to be tied together financially. Court records show Barrass owes money to Marion Stadium LLC, one of Cabaness’ corporations. In a lawsuit, the corporation is listed as a lienholder on Barrass’ property in the STAR district as well as on two businesses and his farmland.

Barrass in August said he didn’t do any work on the project, but he had “moved dirt around.” He said the work he did was not done on the STAR Bonds project, but on a separate “sports complex” project.

But records show that Barrass’s companies were paid for construction work on the STAR Bonds project.

Illinois Answers and Capitol News Illinois obtained reimbursement records from the city of Marion showing Barrass’ companies were paid nearly $1.8 million for work on the project between 2021 through March of this year. Barrass is the owner of several construction companies in and around Marion, including Black River Contracting, Odum Concrete and Stotlar Lumber Company. The majority of the $1.8 million is split between Black River and Stotlar.

Barrass’ reimbursement of $1.8 million was out of $54 million spent on the STAR Bonds project through October of this year.

High-profile government and business leaders sold land for the project, according to city documents. Diederich Properties, whose president is Margaret Diederich, the wife of Williamson County Sheriff Jeff Diederich, received $3.5 million. The sheriff said he had owned the property for decades and reluctantly agreed to sell it so as not to impede the project’s progress.

Marion Heights II Inc., whose president is local accountant and developer Douglas Bradley, received $4.5 million. Phillip Campbell, the former owner of the Marion Harley Davidson store, received $5.3 million.

Another $6.8 million went to Mammoth Sports Construction, the company that will build a fieldhouse with a “Top Golf-like” facility, owned by Jake Farrant. Interest payments totaled $1.1 million.

Millennium Destination Development also received $2.2 million in “professional fees.” Black Diamond and Oasis received $1.3 million.

Who pays if this project fails?

Ultimately, the investors who purchased the bonds will suffer the financial loss if the project tanks. Stifel, Nicolaus & Company Inc., based in St. Louis, underwrote the bonds.

University of Colorado professor Geoffrey Propheter holds a doctorate in public policy and public administration and studies sports facility economics. He’s not so sure about STAR Bonds or about the Marion project. He wonders whether powersports and Harley Davidson can pull customers in from other states.

“You’re going to attract more people with a Costco,” Propheter said.

Recent weak jobs reports made some economists warn of a potential recession, when discretionary spending levels on expenses like leisure vehicles drops. Propheter’s concern with projects like this is that investors don’t like to eat losses, and they also don’t forget about eating losses. The issuer of the bonds — in this case, the city of Marion — will eventually have to pay.

“And how do they make you pay for it? By making your future debt more expensive by asking for higher interest rates in the future,” Propheter said.

Moake said the project’s success or failure would not impact the city’s ability to borrow money in the future. Illinois Department of Revenue spokeswoman Maura Kownacki said the state’s bond rating will not be affected.

Kownancki said no one at the revenue department was aware of the foreclosure suits prior to receiving an email from a reporter. She also said the statute does not require the master developers to notify the department if one of the developers has to drop out.

If the project succeeds and the youth-and-power sports playground Cabaness and Zimbro envision brings hordes of families to southern Illinois, when the bond period ends in 30 years, the city and state will receive the sales taxes generated by businesses in the district.

In early October, Cabaness and Zimbro unveiled the first part of the project. Inside the former Illinois Centre Mall, which will now be known as the Marion Oasis, Zimbro showed local media the first portion of what he called a “big-boy toy store” with dozens of side-by-sides, motorcycles, and a couple of recreational vehicles.

Rich McVicar, a retired state employee who lives in Marion, strolled through the showroom on a Friday afternoon and said he knows enough about the project to be comfortable.

“There’s going to be tax money invested for infrastructure and, eventually, we will have to pay for that, but you have to make an effort to do things like this to make sure the community grows,” he said.

Though 30 years is a long runway for the district, Barrass’ time to deal with banks is running out. Carley, the financial advisor hired to help Barrass secure secondary financing, promised on a Thursday afternoon in mid-September to talk to reporters about a deal he would have completed by the following afternoon that would “straighten out Mr. Barrass’ life and the city.”

That Friday, and multiple times since, he couldn’t be reached.

This article first appeared on Capitol News Illinois and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.