Echoes of the Prairie

Here is where you will find written scripts and bonus information for episodes of Echoes of the Prairie.

Echoes of the Prairie features the history of places in TSPR's broadcast region. Echoes of the Prairie airs Tuesday - Friday at 8:19 am and 5:48 pm. Each episode features content created and recorded by local residents. For more information about the program's content contributors please visit the show's home page.

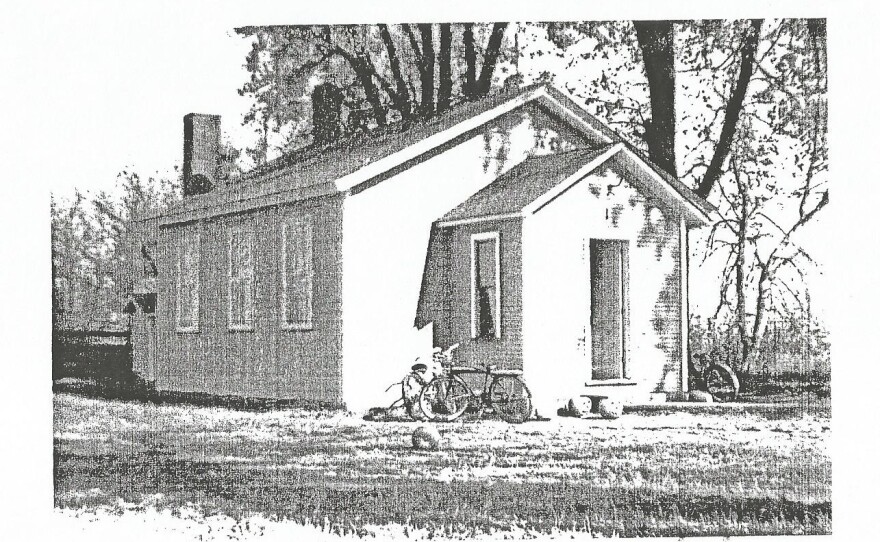

Warren County's One Room School Houses

Back in the day, long before yellow buses rattled down rural roads, much of the schooling in Warren County happened in humble one-room buildings scattered across the countryside.

In 1854, a small village was laid out amid rolling farmland in Warren County. In 1866, just a dozen years after the town of Kirkwood (then called Young America) was founded, the village’s “official” school was built. It was called the “Old South School”.

But beyond the village, 1878-era records show that rural Warren County was dotted with dozens of these “country schools” One room, wood framed — serving farming families spread across the countryside. By some counts, there were well over a hundred ungraded schoolhouses in the county. Inside one of those country schools, a single teacher would ring a bell to start class, gather students around a pot-bellied stove for warmth in winter, call out spelling lessons or arithmetic problems, lead recitations of history or scripture.

The Old South School hosted spelling bees, evening programs, and town gatherings. The one room serving as Kirkwood’s classroom, meeting hall, and social center all at once.

As Kirkwood grew with the railroad arriving, new families settled in and the tiny building couldn’t keep up. By the late 19th century, larger and more modern school facilities appeared, eventually replacing the original one-room schoolhouse. But that first little building on the south side of town lit the spark. It taught the first generations of Kirkwood’s students and set the foundation for the strong community the village is known for today.

In 1908 alone, Illinois still had over 10,000 rural one-room schools. These buildings remain a powerful symbol of simpler times: of multi-age classrooms, impromptu recess in open fields, community gatherings, holidays marked with potluck dinners, and a shared dedication to learning.

Galesburg - Brick City USA

You can't go far in Galesburg without walking or driving on a Purington Paver brick. But the town was built on thick prairie dirt... and through much of the 1800s, every rain turned dusty streets to impassable mud.

Fortunately, below that prairie soil lay thick beds of clay. In 1849, the first brickmaker, German immigrant Henry Grosscup, bought land just east of Galesburg from Knox College. He then sold bricks to the college for its new buildings. The first of many brick streets in Galesburg was laid in 1884.

In 1890, Grosscup's property became the home of Purington Brick Company. Its namesake product, the hefty Paver, measured 4 by 4 by 8 inches and

weighed close to ten pounds. At its peak, Purington fired more than 150,000 bricks a day, in

ovens that covered 300 acres.

By the mid 20th century, however, road builders switched to asphalt. The company closed in the 1970s,but not before billions of Purington Pavers had shipped worldwide, from

Chicago to Paris... Panama City to Bombay, India... and Galesburg had laid over sixty miles of brick on every major street in town.

This episode was written by Peter Bailley with help from Barbara Schock.

Quackscam Fest

“The Great Raid of Dec. 3rd, 1980,” was the event that led to the arrest of 30 men who were charged with poaching in Browning, Illinois. Only one of these hunters went to prison, but many suffered fines and lost access to hunting licenses.

The event shocked and aroused the area. MOST felt it was an intrusion on a way of life that had been present since the first people arrived in the region. So, Browning organized the Quackscam Festival.

The first annual Quackscam festival was held on Saturday, October 3rd, 1981. Quackscam was an all day event that featured a parade, food vendors, a carnival, a duck calling contest, bale bucking, bingo, and a crowning of “Little Miss Browning” contest. These events changed throughout the years. The last Quackscam Festival was held on October 3rd, 1992; and after eleven years the festival was disbanded.

Nevertheless, the event is still widely discussed and part of the local lore. Even today, one might see an old Quackscam trophy in someone’s home or even a copy of the Quackscam game. Hunting and fishing is still a way of life for the people of Browning, IL, and of course it is all done legally.

This episode was written by Emma Weber of Rushville Industry High School

The Elephant's Graveyard.

A myth about where elephants go to die. A metaphor for a place where people or things are forgotten or lost.

Draw a line through Illinois from Monmouth to Oquawka and just maybe you've found that mythical place. Or part of it.

Elephants wander in and out of American history. Jefferson hoped to find them west of the Missouri. There were none. The King of Siam offered Lincoln elephants. Lincoln said no.

Nizie was a male dwarf Indian elephant. Magic brought him to Monmouth. The magic of The Great Nicola, a renowned traveling magician who made Monmouth his home when he was not on the stages of the world. A gift from an Indian prince, Nizie was part of Nicola's traveling magical menagerie. Nizie grew ill in 1934, came to Monmouth for care but died in the fall and was buried forgotten in a pasture.

Norma Jean was a large African elephant and main attraction of the Clark and Walter Circus. She was beloved for her gentle nature. In July of 1972, tragedy and lightning struck Norma Jean. The circus left hurriedly. Due to her size, Norma Jean was buried by the town where she fell. A search for Nizie's grave a few years ago may have found it.

Norma Jean's grave is marked and celebrated by the town still.

This edition was written by Joel Ward

SOURCES

Jefferson's Old Bones

https://www.americanscientist.org/article/jeffersons-old-bones

Lincoln to Thai king: Thanks but no thanks for the elephants

https://www.sj-r.com/story/news/2018/04/01/lincoln-to-thai-king-thanks/12849296007/

Nizie the Elephant

https://www.wchistorymuseum.com/nizie-the-elephant.html

Norma Jean, we hardly knew ye

https://www.peoriamagazine.com/article/norma-jean-we-hardly-knew-ye/

Norma Jean, Elephant Killed By Lightning

https://www.roadsideamerica.com/story/3619

Burlington Inventors

Cross-breeding of animals and plants was a significant hobby for early Burlingtonians – especially the wealthy. Think apples from James Grimes and Charles Mason. Or how about horses from the younger Charles Perkins?

But inventions became even more laudable. The most notable names in this category are Robert Noyce and Wallace Carothers. Both were born in Burlington but, by school age, their families had moved on to other Iowa cities. Burlington claims them anyway.

For Robert Noyce, think integrated circuits and silicon microchips. Following those developments, he co-founded Intel. His nickname says it all: “The Mayor of Silicon Valley.”

Wallace Carothers, on the other hand, was a chemist. At DuPont, his work was with polymers and, by 1939, women were able to switch from silk stockings to nylon stockings – thanks to Wallace Carothers.

This episode was written by Mark Krohlow

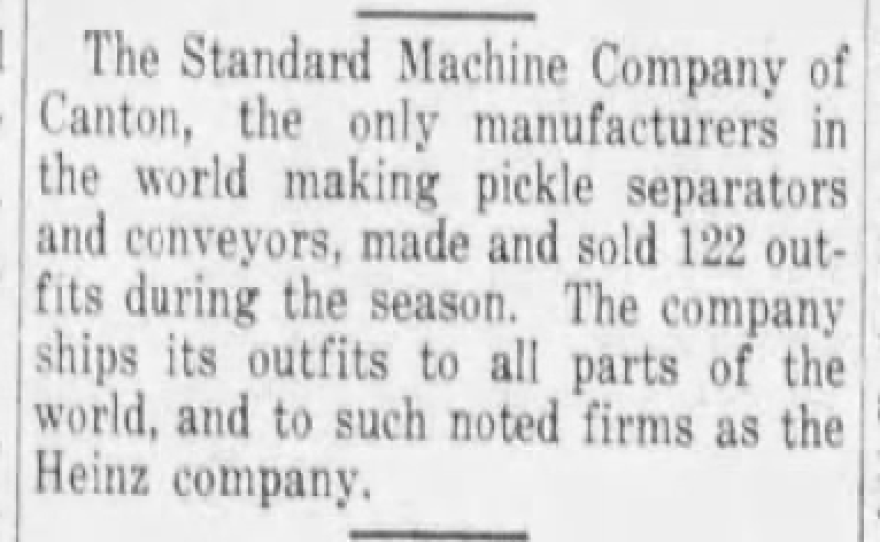

Canton's Pickle Sorting Machine

Canton Missouri has been a great friend to the pickle. Companies like Heinz had marketed them since the 1870s and demand boomed as the country grew. “Pickles Pickles Pickles! We want to contract for more pickles!” screamed a large ad for the Canton Pickle Co. in 1900. Area suppliers literally couldn’t get them out the door fast enough. Some Canton entrepreneurs determined to change that.

Among the more than 7 million patents filed during the 20th century was number 1190067, “the National Pickle Sorter” developed by Standard Machine Co, in 1916. Brothers J.C., J.A., and H.H. Zenge along with their partner T.C. Yeager, conjured a pickle-grading machine enabling rapid and accurate sorting, noting in the application “The invention aims to provide novel means for initially sorting the pickles, and to provide a cooperating means adapted to separate the sorted masses of pickles from each other as they drop downwardly.”

Demand was almost immediate. Standard Machine shipped twenty across the Midwest in the first year. Within a decade they produced fifty, aided by the National Pickle Factory Association of America’s official recommendation.

The nation’s appetite for canned food soared due to improvements like heat sealing and demand caused by World War One. Feeding soldiers and civilians was crucial to both morale and victory and was now needed on an immense scale. Such improvements in industrial canning helped make perishable food available like never before.

Standard Machine Company changed America’s canning industry, making it easier for farmers and suppliers to provide cucumbers, brought canned pickles to more people at home and abroad, and helped feed our soldiers.

In time, other companies and other inventions replaced Standard Machine and its National Sorter. The factory closed in the 1980s, its building on Lewis Street was destroyed by fire in 2013, and today few seem to know about Canton’s important pickle sorter. But for a time in the 20th century it taught the world a lot about the Art of the Dill.

This episode was written by Scott Giltner.

Hotel Nauvoo

When you mention Nauvoo today most people will think of Hotel Nauvoo the world famous buffet that is a Nauvoo tradition. The original building was built as a residence in 1841, but in 1885 William Riembold purchased the home and converted the property to the Oriental Hotel adding nine rooms for guests. William and his wife ran the hotel until

1940 and then the building was vacant for a number of years. In 1948 John A. Kraus bought the dilapidated structure and after returning the building to its former glory he opened Hotel Nauvoo with buffet and restaurant on the first floor and rooms upstairs. In 1961 the building next door was connected to add more dining area, and 1968 had another dining room built on. Today the buffet is still serving food like it did in 1948 and is still owned by the Kruas family.

The Kraus Family made the decision to close the hotel and restaurant after this episode was written and recorded.

This episode was written by Rebecca Williamson.

Lincoln's Wrestling Matches

It is a fact that Abraham Lincoln is in the National Wrestling Hall of Fame because of his victory against the bully of New Salem … Jack Armstrong. It is also said that Lincoln only lost one wrestling match in the twelve years of his youth when he partook in the sport. And did you know the only match he lost was in Schuyler County, IL, and in fact, he may have lost twice?

In 1832 at the beginning of the Black Hawk War, 23 year old Capt. Lincoln led his men into camp just north of Rushville. After a dispute over a bivouac site, it was decided that Lincoln and Dow Thompson would “wrassle” for the right to camp. Lincoln said, “I then realized from his grip that for the first time that he was a powerful man and that I would have no easy job. The struggle was a severe one, but after many passes and efforts he threw me.”

Furthermore, according to William L. Wilson, a volunteer from Rushville, he and Lincoln also engaged in a wrestling match.

In 1882, Wilson wrote to the Adjutant General of Illinois and recalled the days of the Black Hawk War, “I have during that time had much fun with the afterward to be President of the United States ... I remember one time wrestling with him.Two best in three, and ditched him.”

If we are to believe Wilson then Lincoln was defeated twice and both losses were in Schuyler County.

This episode was written by Brian Schmidt

WSBV Radio and Clyde Hendricks

In the mid 1920’s Maquon had “radio fever.” WSBV, a radio broadcasting station, was operated by Clyde Hendrix in 1925 and

1926 from his cream testing station located on East Third Street in Maquon. If not the first, WSBV was one of the earliest radio stations in Knox County. The call letters stood for World’s Smallest Broadcasting Village. As promoter and operator, Clyde announced, “This is Station WSBV, world’s smallest broadcasting village, located on the banks of old Spoon River, where the bandstand stands in the middle of the town, the hard road runs all the way ‘round; everyone lives in the 100 block and your dog’s no better than mine.” Telephone requests came in for Ruth “Sugar” Forquer and her ukulele, and for the Selby sisters, Helen and Grace, who sang. Others wanted to hear Raymond Housh play his fiddle or listen to Harold Allen and Charlie Tomlinson, who were good on the mouth organ or jew’s harp. Anyone with a talent was welcomed, including Clyde’s hound dogs, always on hand to do their bit.

This episode was written by Kenny Knox.

Keokuk Armory Fire

Just after 9:30 PM on Thanksgiving Eve 1965, an explosion and flash fire tore through the National Guard Armory, where families had gathered for a night of square dancing. The blast collapsed the roof, trapping many inside. Seven died that night, over fifty were injured—some hospitalized for months. The final death toll reached twenty one.

Nearby residents rushed to help. Local medical workers treated the injured, contractors brought equipment, and the community rallied to donate blood, time, and labor in response to the tragedy.

Beyond local aid, people across the country—and even abroad—offered support. Patients were flown out for specialized care, news coverage spread far and wide, and donations came from places as far as Germany and Australia. Square dance clubs across the country reached out to help the victims and their families.

Investigators later determined the explosion was caused by a broken pipe leaking natural gas which was then ignited by a water heater.

As time passed, survivors began returning home, forever changed by the events of November 24, 1965—a day remembered for both its tragedy and the remarkable unity it inspired.

This episode was written by Angela Gates of the Keokuk History Center.

Christopher Columbus Clark

In Canton Missouri’s Forest Grove Cemetery, just off of highway 61, can be found the grave of Civil War veteran Christopher Columbus Clark, a man with some pretty surprising historical connections.

Born in 1846, Columbus Clark was raised in Canton. His mother Elizabeth Davis was cousin to Jefferson Davis. At 18, Unionist Clark enlisted in the 69th Enrolled Missouri Militia, formed in response to Confederate raids by guerilla commander Joseph Porter, serving as a private through portions of 1864 and 1865.

After the war he married Susan Overall, born the daughter of a minor slaveholder in Kentucky, and they had five children. Later, Columbus moved to Kansas to live with his daughter Gabriella, her husband Harry Armour and his granddaughter Ruth. Ruth married Ralph Dunham and had a grandson, Stanley Dunham. Columbus would pass away in 1937 at age 91 and was returned to Canton for burial.

Stanley Dunham married his sweetheart Maddie Payne in 1940. Maddie gave birth to a daughter named Stanley Ann, (known as Ann), in Wichita. In the late 1950s the Dunhams moved to Hawaii where Stanley got a job at a furniture store. In 1960, Ann Dunham met her future husband, a University of Hawaii student named Barack Obama, with whom she had a son born August 4, 1961 that you may have heard of.

So in Canton Missouri’s Forest Grove cemetery lay Civil War veteran Columbus Clark, cousin to the President of the Confederacy and 3rd great grandfather to the 44th President of the United States. Those relationships are a reminder that history connections are everywhere you look, even in small town Northeast Missouri next to the old Pizza Hut.

Born in Monmouth, Bound for Legend, Wyatt Earp

In the quiet heart of Monmouth, Illinois, stands a modest white house with green shutters. It’s the Pike-Sheldon House. At first glance, it looks like any other 19th-century home, but in 1848, it became the birthplace of one of America’s most legendary lawmen: Wyatt Earp.

Before the dusty streets of Dodge City and the gunfight at the O.K. Corral made him a frontier icon, Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp was just a boy growing up among the rolling prairies of western Illinois. His family’s home right in Monmouth still stands as one of the few places where visitors can literally walk in the footsteps of the man who would help define the Wild West. Wyatt Earp is a Monmouth son of the Heartland who became a national figure for his role in taming western frontier towns.

The Pike-Sheldon House isn’t just a birthplace, it is a time capsule. Its simple wooden frame has seen the growth of a nation, the movement of pioneers, and the rise of a legend whose name would echo from Illinois to Arizona and beyond.

Today, Monmouth honors that connection. It is a small Midwestern town that helped shape a larger-than-life American story. The Wyatt Earp Birthplace draws visitors, historians, and Old West enthusiasts from across the country.

Often heroes of the Wild West came from small, hardworking Midwestern communities. Because before he was a lawman and a legend, Wyatt Earp was one of Monmouth’s own.

The episode was written by Ann Tenold

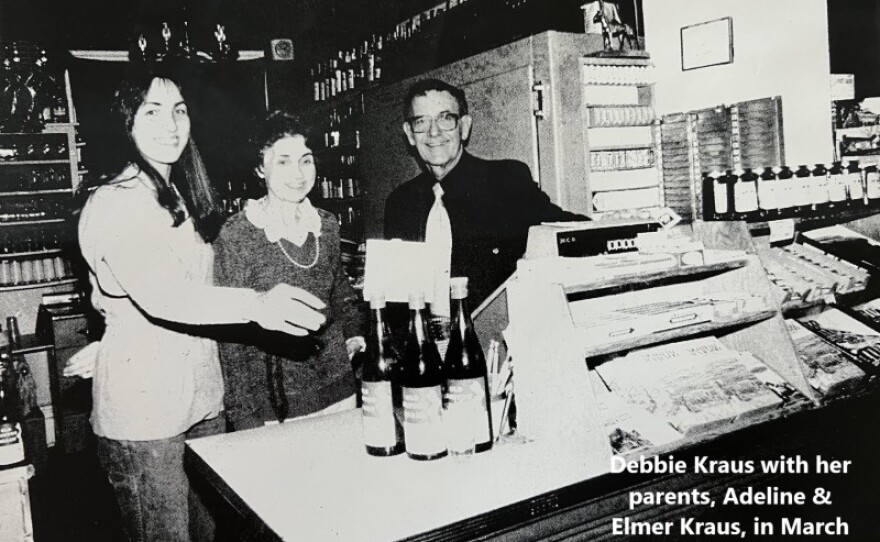

Oldest Continuous Pharmacy in the Nation?

In 1834 Dr. J.B. Clarke opened a drug store on the north corner of the west side of the public square in Rushville, IL. This location has been a “drug store” ever since.

In 1838, Clarke sold out to James G. McCreery, who continued the site's tradition until his retirement in 1883. It was then sold to Isaac N. Vedder. The Vedders ran the store until 1955 when it was sold to Clark Moreland. In 1960, Clark’s brother-in-law, William Devitt, purchased half the interest. Ever since the store has been known as Moreland and Devitt.

The original building was a log cabin and thereafter a one-story frame building was constructed. The cabin was moved to Monroe Street and eventually a frame home was built around it. In 1976, the home was torn down and still inside was the old “drug store” log cabin. The frame building survived until 1904, when Emma Vedder had the building torn down and a massive two-story brick building built. It still stands on the west side of the public square where Congress and Washington Street intersect.

Current owner, Garry Moreland, has researched the topic, and cannot find an older continuous site in the nation. Therefore, Rushville can claim the title as having the oldest continuous “drug store” in the nation.

This episode was written by Brian Schmidt.

When Grocery Stores Were Scandalous

Today, the term _grocery_ has a quaint, small-town ring. It's often paired with the word _neighborhood_. But in the 1800s, grocery also meant liquor store. Controversial.

In the Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858, Stephen Douglas referred to Abraham Lincoln as a -- quote -- flourishing grocery-keeper in

the town of Salem. Lincoln recognized an insult, and he replied that he had -- quote -- never kept a grocery anywhere in the world.

Although Galesburg was founded by anti-liquor fundamentalists, by the 1880s the city had 22 grocery stores. There were also 15 saloons, then known as sample rooms, that served liquor by the drink. Respectable women didn’t go into saloons, but from the grocer or druggist they could purchase concoctions such as Hostetter’s Bitters or Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound. These alcohol–based patent medicines were unregulated, widely advertised, and relatively inexpensive.

After prohibition ended in 1933, the word saloon faded from use, in favor of uptown terms such as tavern or cocktail lounge, and a grocery was something everybody wanted in their neighborhood.

This episode was written by Peter Bailey with help from Barbara Schock

Joseph Smith Homestead

In the spring of 1805 William Ewing set out to set up a trading post for the US Indian Affairs office. He cut down several oak trees on the peninsula that is now called Nauvoo and built a two story block house by May of 1805. Ewing managed the post for a short period of time, but it was closed due to mismanagement. A series of Indian Agents came through to open the trading post for short periods of time, but by 1810 the building sat abandoned and vacant. In 1824 Captain James White purchased the land and cabin and reopened the trading post. On May 10, 1839 Joseph Smith and his wife Emma would move into this log cabin after purchasing it from Captain White. This building still stands today and is called the Joseph Smith Homestead. Joseph expanded it several times for his growing family and growing church needs. Today the building is owned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and is open for tours.

This episode was written by Rebecca Williamson

Billy Sunday

Without a doubt, Burlington lived up to the reputation of river towns. The refined class was eclipsed by the ruffian class. Vast quantities of alcohol resulted in frequent brawls and even in shots being fired.

In 1905, Burlington was ripe for an appearance by Billy Sunday, the most notable evangelist of the time. In preparation, a temporary tabernacle was built. It seated four thousand, was 163 by 69 feet, and required forty wagon loads of sawdust to serve as the three-inch-thick floor. Because the five-week revival was to be in November and December, six stoves were placed inside for heating.

Billy Sunday had already made a name for himself as a professional baseball player. Playing initially for Chicago, he was reputed to be the fastest man in the National League – circling the bases in 14 seconds.

After his 1886 conversion, Billy went on the evangelism trail. Pulpit acrobatics served him well. Favored targets were the “red-nosed, buttermilk-eyed, beetle-browed, peanut-brained, saloon-keepers,” quoted the Burlington Gazette. One day, with a few free hours, he acted as timekeeper at a Burlington-Winfield football game. When a scuffle broke out, he quelled it by “flinging men right and left.”

The revival was a success with 2,500 people being converted. Records don’t show how many stuck with the conversion.

This Episode was written by Mary Krohlow.

Caroline Grote

No woman shaped Western Illinois University’s early years more than Caroline Grote. Born in 1863, she spent 56 years in education, breaking barriers as Illinois’ first female county superintendent.

In 1906, when Bayliss was president of Western Illinois State Teachers College, he hired Carolyn Grote to train school teachers. But she also advocated for improving conditions in rural schools. In one report, she noted that many schools had windows that “were seldom washed,” and outhouses that were deplorable. School libraries were often inadequate and not suited to the needs of the students.

Grote’s career took a new turn in 1908 when she became the Dean of Women and supervised the women students. One rule she upheld was that “every modern girl should have a chaperone.”

Even at 69, Caroline Grote never stopped learning, earning a doctorate from Columbia University. She retired in 1935, and to honor her impact, WIU renamed Monroe Hall to Grote Hall, ensuring her legacy lives on.

This episode was written by Sue Scott.

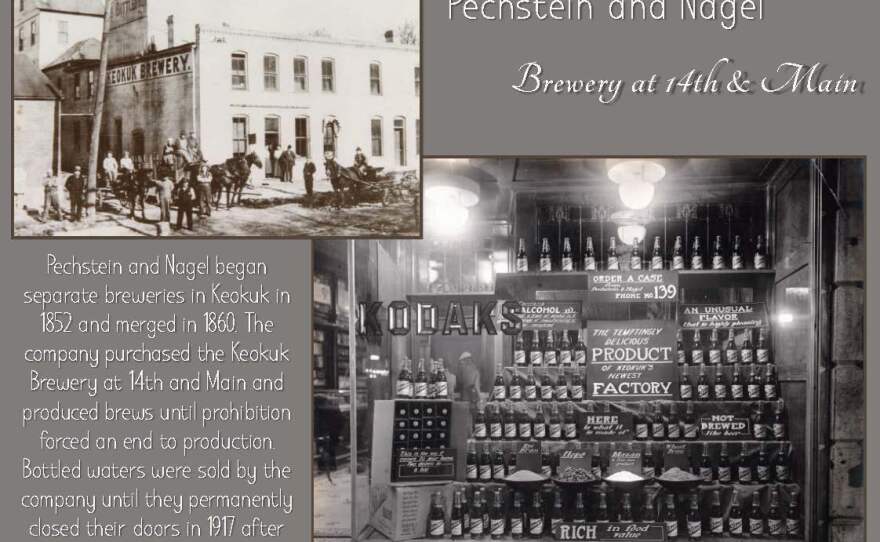

Keokuk Breweries

In 1973, the discovery of caverns beneath a yard on Plank Road in Keokuk brought to light the town’s rich history of beer and whiskey production.

Around 150 years ago, Keokuk had five breweries and seven distilleries. Keokuk’s first brewery was built in 1850 between 12th and 13th on Main Street. It was owned by William Schowalter. Joseph Kurtz would begin brewing at this location after taking over in 1855. He called it “City Brewery” and moved the operation to 19th and Plank Road by 1861. The Leisy Brewing Company was an impressive-looking operation along the riverfront in West K and Pechstein and Nagel’s Keokuk Brewery occupied the north side of the 1400 block of Main Street. They operated until January 1, 1916 when Prohibition was enacted in Iowa. Other breweries in Keokuk’s history included Kennedy and Vockrodt Ale, Eagle Brewery, Mississippi Brewery, Peter Haubert Brewery, Frederick Letterer, and F. W. Anschutz. Distilleries included Martin Keating, N. Leonard and Company, John S. McCoy, and Stannus and Evans.

Saloons promoted locally produced beer and whiskey, and beer gardens featured musical talents to attract patrons who would enjoy Keokuk’s brews.

Fires wiped out many breweries and by 1900, only two remained. When those remaining operations closed, so did a chapter in Keokuk’s manufacturing history.

This episode was written and voiced by Angela Gates of the Keokuk History Center.

Poe ain't comin'

"Poe ain't comin'."

That's what they might have said in 1849 in Oquawka, Illinois.

Edgar Allan Poe had already made "The Raven" croak and "The Tell-Tale Heart" beat by 1848 but the Mississippi River town of Oquawka, Illinois, wanted Poe not for his poems and tales but for his fame as an editor and the prestige Poe would bring to the new Oquawka Spectator.

Twenty year-old Edwin Patterson, son of The Spectator's founder, was a Poe fan. Patterson wrote Poe in December, 1848, inviting him to the edge of the Midwest and the beginning of the West. Poe could make The Spectator the literary heart of the nation, Patterson hoped. Oquawka had high hopes for itself too. Civic pride and boosterism were bulwarks of 19th century small town presses.

The life of a magazine editor in 19th Century America could be prestigious as well as precarious. The toast of a town or the nation one moment or falling deeper than the House of Usher the next. Patterson and Poe corresponded for months, with varying degrees of enthusiasm on the part of Poe.

Finally, circumstances intervened. Patterson waited for a letter that never came. Edgar Allan Poe died under strange circumstances in October, 1849. Poe was 40 years old.

Patterson soon caught the gold bug and left for California. The Spectator continued publication until 1908.

This edition was written by Joel Ward and voiced by Joel Ward.

SOURCES

Might Edgar Allan Poe have made Oquawka a literary hub?

Jeff Rankin

https://jeffrankin.medium.com/might-edgar-allan-poe-have-made-oquawka-a-literary-hub-6ea6e8c31091

What if Edgar Allan Poe had moved to Oquawka?

Rex Cherrington

https://www.thezephyr.com/poequawka.htm

IMAGES

Edgar Allen Poe

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edgar_Allan_Poe

Edgar Allen Poe

Encyclopedia Britannica

https://cdn.britannica.com/52/76652-050-F4A6B093/Edgar-Allan-Poe.jpg

River Scene, Oquawka Illinois

Henderson County Library

https://www.hendersoncolibrary.com/oquawka/mississippi-river/

W.A. Sheaffer and the Birth of an Iconic Pen Company

In 1907, a Fort Madison jeweler named Walter A. Sheaffer revolutionized the way people wrote. Frustrated with the messy and inconvenient fountain pens of the time, Sheaffer invented a self-filling pen using a lever system—eliminating the need for separate ink bottles. With just $35 and an idea, he filed a patent and set out to change the writing world.

By 1912, Sheaffer Pen Company was officially founded right here in Fort Madison. What started in the back of his jewelry store quickly grew into a global brand. Sheaffer pens became known for their craftsmanship, innovation, and reliability—earning a reputation that made them a favorite among writers, business leaders, and even U.S. presidents.

For nearly a century, Fort Madison was home to the world headquarters of Sheaffer Pen Company. Though production has moved, the legacy of W.A. Sheaffer lives on. His innovation didn’t just put Fort Madison on the map—it made an indelible mark on history, one signature at a time.

Episode was written by: James Lemberger

Monmouth Western Stoneware Company

Welcome to Monmouth, Illinois, where a quiet patch of land once hid a discovery that would help shape an American industry. In the 1850s, as farmers tilled the soil, and more railroad tracks began laying west, a treasure beneath their feet was discovered. It’s not gold, not silver, but clay. And not just any clay. This was a rich, remarkably workable deposit perfect for pottery and stoneware.

Local entrepreneurs quickly realized what they were standing on. Word spread, kilns were built, and before long Monmouth became a hot spot for high-quality clay products. But the real breakthrough came in 1906, when several regional potteries joined forces. Their merger formed a name that would become legendary in American ceramics: Western Stoneware Company.

Western Stoneware wasn’t just making jugs and crocks. Potters were crafting the everyday vessels that fed America: butter churns, food storage jars, water coolers, and later, decorative pieces that collectors now hunt for like buried treasure.

And it all started with those extraordinary Monmouth clay beds. Raw material that ignited a company, fueled a region, and left its mark in every beautifully glazed piece of Western Stoneware.

Episode written by Ann Tenold

Virginia “Jennie” Scripps

Eliza Virginia Scripps or Miss Jennie as she was known, was born on October 10th,1852, in Rushville, IL. While her older siblings were off starting and running newspapers all over the United States, Miss Jennie remained in Rushville, caring for her parents and their farm. She remained on the homestead until her parents passed and fire destroyed the original home in 1897. She then moved to California, but also bought a home in Rushville on West Lafayette which still stands today and is the home of the author's grandparents.

Her commitments to the town are still recognized today. In 1909, she had the Episcopal Church built in remembrance of her father; and Scripps Park was created from the Scripps Homestead, which she had turned over to the city of Rushville to be used for a park or recreation. Her sister, Ellen Browning Scripps, celebrated Miss Jennie by having The Virginia (a replica of the original home) constructed near the original site.

Miss Jennie’s kindness and dedication left a lasting mark on her hometown of Rushville. She gave back to the community creating landmarks and spaces still respected today. She died in London, on April 28,1921, and is buried in Rushville.

Episode written by Reed Fretueg, Rushville Industry High School Student

How Loraine, Illinois got it's name

The town of Loraine was started in 1870 on the Carthage branch of the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad. Like many small towns in Western Illinois at that time, it was started as the result of the railroad coming through the prairie. Anthony Pitzger Lionberger worked for the CB&Q railroad and helped put the railroad line through the area that became Loraine. The residents admired Anthony so much that they named the town after his daughter Loraine who was two at the time. In August of 1873, at the age of 40 after jumping off a train onto a railroad spike, Anthony sadly passed away from blood poisoning. Little Loraine lived a long full life eventually passing away in 1952 at the age of 83. Anthony Pitzger Lionberger is my 3 times great Uncle.

Episode written by: Rebecca Williamson

The Pearl Button Capitol of the World

Walk around the riverfront in places like Canton Missouri these days and you can still find peculiar little shells, polished smooth, with several small holes cut in them. Younger people are puzzled but older folks know them as relics of a once powerful industry and of an age before modern plastics when freshwater mussels were central to the region’s economy.

In the early 1900s, this part of the Mississippi was the “pearl button capital of the world”. The largest producer, the Hawkeye Pearl button factory in Muscatine Iowa, specialized in mother-of-pearl buttons and other pearl novelties, producing at its peak a staggering 1.5 million mother-of-pearl buttons a year.

Clammers collected mussels and worked in camps along the river to open them and remove the meat and pearls. In cutting plants in Canton, Keokuk, and Oskaloosa the raw shells were processed. Some cut the shells into squares, while others polished, drilled the holes, or machined decorative designs. At its peak, the Hawkeye Pearl Button Factory had more than 800 employees.

Eventually, as Mississippi mussels were fished to scarcity, zippers and other closures became more popular, and mass-produced plastic buttons came to dominate, the pearl button trade died out. Canton’s Hawkeye Pearl button factory closed in 1960. The last Muscatine pearl button was produced in 1967. Today a 28 foot tall statue of a clammer stands in Muscatine as tribute to the workers who built what was once a $1 million a year industry at a time when more than a third of the world’s buttons came from our area.

Episode written by Scott Giltner

The Naming of Burlington, Iowa

Other than the fur traders who reaped untold riches in their trade with the Fox and Indians, it was 1832 when the earliest settlers were allowed west of the Mississippi. The area which would become Burlington became a popular site. In 1833 streets were being laid out. John B. Gray bought one of the first lots and opened the first grocery store. He also acquired naming rights and settled on Burlington - in honor of his Vermont home town. Prior to the official naming, the area had been known as Shoquoquon - meaning Flint Hills.

Then in 1859, several Wisconsin and Burlington people became part of the Colorado gold rush. There were Alonzo Allen and Henry Dickens, George and Morse Coffin, and the Beckwith family. They settled along St. Vrain Creek. Some panned for gold – others chose farming. By 1962, a name was needed so that a post office could be established. It became Burlington – this time in honor of Burlington, Iowa. Despite high hopes for the settlement – flooding became an issue – just as at home. There remains an Old Burlington Cemetery, but most residents moved to nearby Longmont.

Episode written by Mary Krohlow